IceCube Neutrino Observatory

The Ghost Hunters

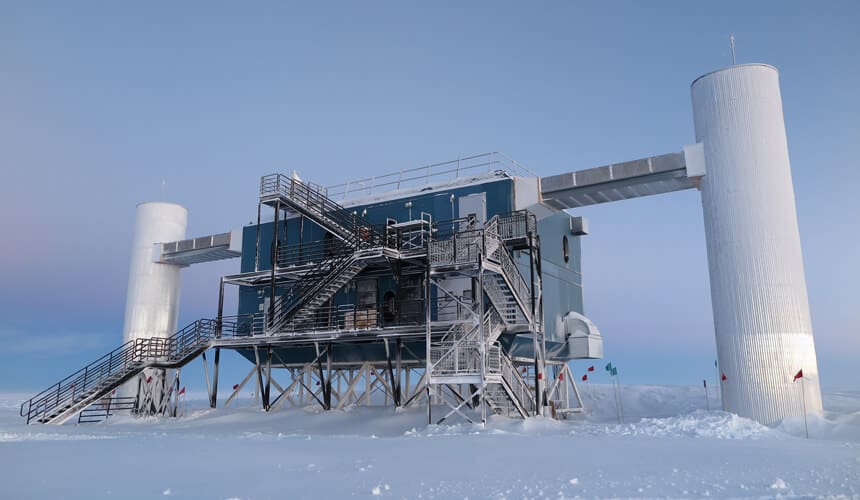

Sometimes, the best way to study the stars is to look … under the ice. Since 2002, the IceCube Neutrino Observatory has helped researchers to look for evidence of neutrinos, the elusive subatomic particles that originate in the sun and the Earth’s atmosphere. Neutrinos are nicknamed “ghost particles” because they can pass through matter mostly undetected, and even though they’re tiny, they could help to explain some big questions about the forces of the universe.

Photo by Bryce Richter.

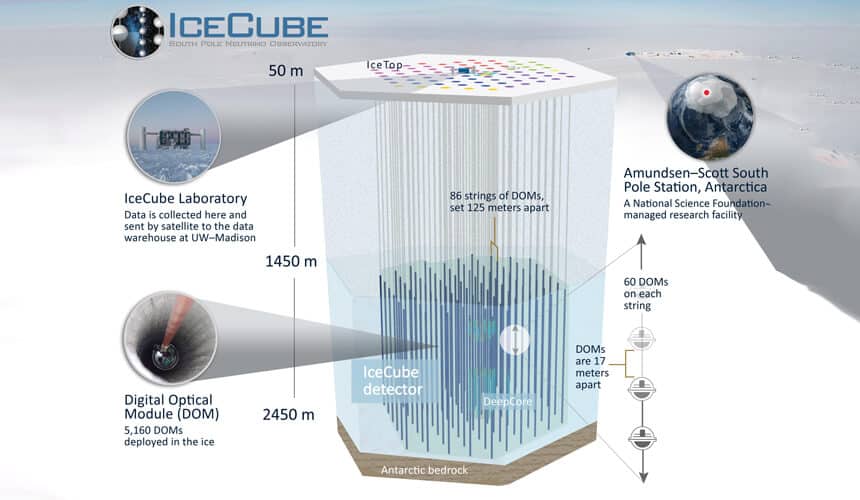

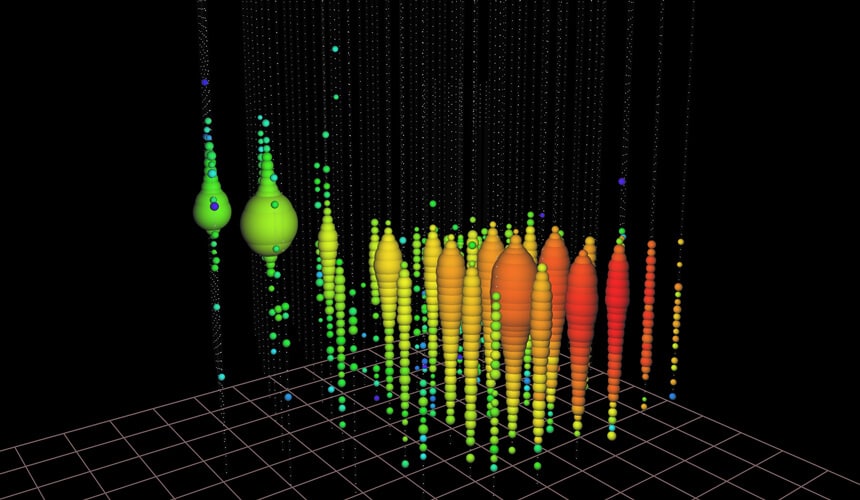

IceCube is made up of more than 5,000 detectors suspended under glaciers near the South Pole. When a neutrino interacts with a water molecule in the pristine, unpolluted ice, it produces a tiny flash of blue light. The IceCube detectors record those flashes and report them back to the rotating collection of scientists who ensure that the research station is staffed year-round. UW-Madison is the lead institution on the project, which is funded by the National Science Foundation and includes 250 collaborating researchers from 10 countries.

In 2013, IceCube found 28 neutrinos that appear to have originated outside of our solar system — the first evidence of cosmic neutrinos. “It is gratifying to finally see what we have been looking for. This is the dawn of a new age of astronomy,” said IceCube’s lead investigator, Francis Halzen, who has worked on neutrino telescopes at the South Pole since the 1980s.

For years, researchers have been especially interested in finding evidence of “sterile” neutrinos, a kind of particle that would explain the balance between matter and antimatter, as well as the origin of dark matter. But in summer 2016, IceCube officially concluded that the data don’t support the idea, meaning that sterile neutrinos do not exist. The finding was a blow to physicists around the world, but it also reopens the door to new theories for understanding the physics of the universe.

And IceCube will be there to help scientists find the evidence.

28° F

28° F