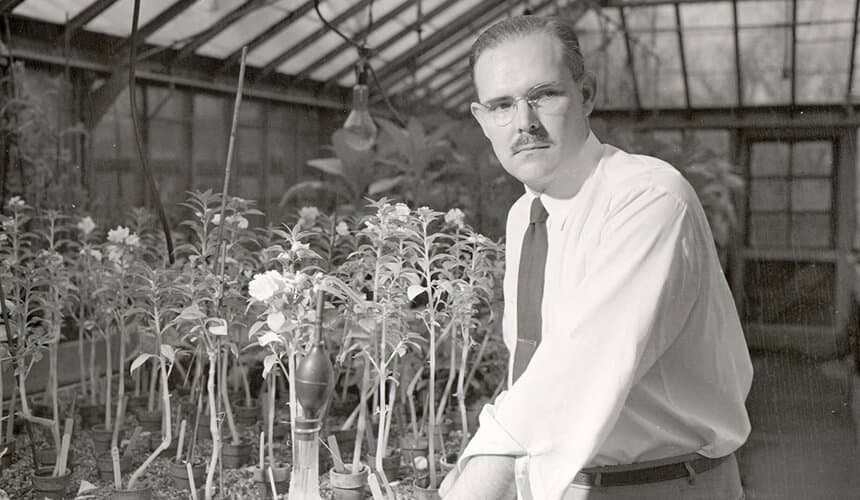

John Curtis

The Original Restoration Ecologist

Bring up conservation in Wisconsin and you’ll often hear the name John Curtis MS1935, PhD1937 along with such innovators as Aldo Leopold.

Image courtesy of the UW Digital Collections Center.

A professor of botany, Curtis was a pioneer of restoration ecology before the term existed. In his relatively short career, the namesake of Curtis Prairie at the UW Arboretum dramatically changed how we study plants respective to their surroundings, and he inspired the protection and restoration of hundreds of Wisconsin’s natural areas.

While growing up in southeastern Wisconsin, Curtis was fascinated by the precise conditions orchids needed to thrive, and his doctoral work at the UW focused on the flower’s physiology.

After graduating in 1937, he began working at the university and remained on the faculty throughout his career, taking leave during World War II to serve as civilian research director in Haiti, searching for alternate sources of latex when fighting in the Pacific rendered rubber plants inaccessible. While in the Caribbean, Curtis noticed introduced species had destroyed many unique native species; once home, he was inspired to learn what’s needed to protect the balance of Wisconsin’s natural plant communities.

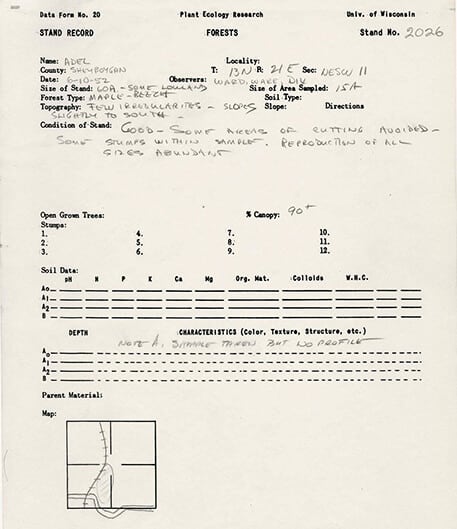

Curtis and his colleagues and graduate students spent years conducting massive field studies at sites where Wisconsin’s prairies once thrived. Their findings, and the revelation that natural communities had indeed drastically changed since pioneers had settled the state, informed his 1959 book The Vegetation of Wisconsin: An Ordination of Plant Communities, sometimes called the “bible of Wisconsin plant ecology.” Many of those carefully curated field data are still used today by the Plant Ecology Lab and researchers worldwide to assess ecological change.

From The Park

Following in the footsteps of mentor Aldo Leopold, Curtis shed profound light on the ecology of Wisconsin’s plant communities and fostered the concept of prairie restoration.

Those studies also led Curtis to develop theories about an innovative technique to restore prairies — prescribed fire — which is now widely used in ecological management.

Curtis was inspired by the vision fellow conservationist Aldo Leopold had for the UW Arboretum: to reconstruct a sample of what Dane County looked like before agriculture became widespread in the 1840s. He proposed using some of that new space as an outdoor lab to examine how communities of plants cooperate.

When Curtis died in 1961, at age 47, the Friends of the Arboretum dedicated the 60-acre prairie that now bears his name at their inaugural meeting. Curtis Prairie is the oldest restored prairie in the world and is home to hundreds of plant species. The site supports research on everything from climate change to pollinating insects.

7° F

7° F